“Working, thinking, fighting, bleeding... - almost forgetful”

Impossible Poiesis and the Counterrevolutionary Amnesia of ‘Marxist’(-)Feminism

Another thing we say about women, alas, is that they are always forgetful. We even call them birdbrains[2] - T. Sankara

In 1871, as Marx penned the quoted portion of the title above, a torrent of working class blood washing over Paris streets had yet to fully exhaust itself. Subsequent generations of the world’s laboring women and men then continued to work and think and fight. In 1987, as Thomas Sankara criticized man’s tendency to misattribute absent-mindedness to women, he too was but a few months away from being shot in cold blood. Presumptions made in contemporary society about prehistoric ‘gender’ dynamics are not necessarily the reason for any of these failures, and the ‘forgetting’ wrought by these historical processes already took place long ago. Marx could look in immediate hindsight at a cataclysmic loss of “La Commune” already in the making. While Sankara, whose entire nation had known some measure of anti-imperialist victory, was still unable to foresee his own impending doom. What both Marx and Sankara share in common, despite being disjointed in time and space, is the perspective that ‘revolutionaries’ are always at risk. This hazard is in misinterpreting or mislaying events and fraying at the edges of historical oblivion. Where then does responsibility rest in holding together the threads of a recent and present with the distant past?

Whether the earliest human societal organization was Communistic and ‘matriarchal’ or not, cultural and political struggles inherited from long ago still linger. A persistent process of misremembering this exact sequence in anthropological time must be at least as important as the spinning of its yarns, archaeological retrievals and opposite-facing textualizations. Walter Benjamin asserts that for Marxists, articulating and intervening in history doesn’t actually mean portraying “’the way it really was.’ For historical materialism, it means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger, danger which threatens both the tradition and its recipients. The danger of allowing themselves to be the tools of the ruling class. The tradition must always be won anew from conformism. The Messiah will also come as the conqueror of the Antichrist, not only as a redeemer.”[3] In the primitive, ancient, domestic and industrial spheres, workers have taken on immense burden and missed many victories. Though as of yet unable to attain ‘salvation’ in the West, the international working class socialist movement’s noble fighting lineage still insists upon collective struggle, and dutifully defies the howling nightmarish weight upon the individual.

“It is the same with the cult of the female as with the cult of nature.”[4]

Class Coincidence

J.J. Bachofen writes during the 1860s that in bygone times,

“[t]he telluric-feminine principle extends further than the male-political one. It defines the [People] according to their material existence, in which the brotherhood originating from the mother is contained.”[5]

Bachofen also wrote a message to Nietzsche in the mid-1870s urging him to, “stay away from everything that is outdated.”[6] This academic obsession with ‘matriarchy’ and its relation to ‘feminism’ has itself oscillated or vacillated in and out of fashionable status for over 150 years. According to Darmangeat and Grosjean, since the period in which Bachofen’s book was released in 1861, for both

“[f]eminists or anti-feminists, no one has resisted the temptation to justify their present choices by assertions about a distant past that they did not hesitate to reconstitute at their convenience.”[7]

Over the same time period, theorists and practitioners of scientific socialism also cooperated in constructing material bulwarks against what is alleged to be an evil and eternally immovable ‘patriarchy.’

In 1934, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Engels’ “Origin of the Family,” major figures in Soviet anthropology had collected and published archival material including letters sent by J.J. Bachofen to Lewis Morgan from the early 1880s. In one of these letters, Bachofen offers Morgan his view of why ‘mother-right’ became so controversial in academic and cultural discourse.

“[Mainstream scholars] propose to make antiquity intelligible by treating it from the point of view of the popular ideas of our day. They see only themselves in the works of the past. Hence their stupidity, which expresses itself in the rejection of all traditions that do not permit themselves to be treated in this way. To understand a cast of mind different from ours is a difficult task: to take barbarism in itself, forgetting everything that concerns our so-called civilization, is considered a sign of a reactionary tendency, both social and political. What is the final result of such vanity? Nothing else than a deplorable and distorted idea of the beginning of human development.”[8]

The Soviet Party Alexander Busygin warned of the rising fascist danger:

“[t]he class enemy is fighting fiercely on the theoretical front. All branches of knowledge studying primitive society have been mobilized in the service of fascist racial theory. It is a matter of honor for Soviet scientists to sharpen and expand the theoretical weapons of the proletariat and, together with it, utterly defeat the enemy in this area as well.”[9]

Less than 10 years before the Soviets published Bachofen’s letters, Nazi academic Alfred Bäumler wrote of Bachofen’s relationship to Nietzsche stating that after Nietzsche declared himself an enemy of Christianity, Bachofen cut ties with him completely.[10] Bäumler also asserts that Bachofen sees a matriarchal prehistory

“mixed with religion and sensuality… [where] the woman is able at times to soar higher than the man… [for Bachofen] [b]eginning and end, myth and history, are one.”[11]

Whereas the late 20th century ‘feminist’ writer Adrienne Rich characterizes this area of study as “a springboard into feminist desire,”[12] Bachofen, importantly here, was seen to have “endowed the feminine with an independent religious and political authority separated from a western civil law.”[13]

Marx in 1868 wrote to Engels stating that

“[i]t’s the same in human history as in paleontology. Things that are right under one’s nose are, in principle, unseen, even by the most distinguished minds, due to a certain judicial blindness. Later, when the time has dawned, one is surprised that what is unseen still shows its traces everywhere… [instead of looking to Romantic and Medieval periods, another tendency which] corresponds to the socialist trend, although [such] scholars have no idea that they are connected with it—is to look beyond the Middle Ages into the primeval times of every people. They are then surprised to find the newest in the oldest.”[14]

This is however not so much of a surprise once such sources are consulted, since it was Bachofen who wrote that

“[t]he end of state development resembles the beginning of human existence. Primal equality ultimately returns. The maternal-material principle of existence opens and closes the cycle of human things. Birds are the oldest birth of the primordial egg, their avian freedom the original state, just as all self-born primal mothers are conceived of in bird form.”[15]

‘Matriarchy’ as a historiographical loadbearing column caused the pederastic National Socialist movement to bristle. Other reactionary ‘intellectuals’ in Weimar Germany clumsily attempted to incorporate or skirt around it. Conservative elitist Berta Eckstein-Diener wrote “Amazons are not simply sporty, bob-haired feminists… Amazonentum is… a heroic means of forming the female world view and keeping it pure in the face of male assaults.”[16] The openly gay anti-Jewish German mystic Alfred Schuler wrote in the 1920s,

“Women should be free; they are often more worthy of it than men... But as far as so-called education is concerned, I am very much against it. The less women learn, the more valuable they are; then they know everything from within themselves.”[17]

In a notable Heidegger lecture from 1943, Heraclitus’ ‘primordial’ connection to the goddess worship in Ephesus is deftly highlighted. Heidegger refers to an anecdote in which Heraclitus is calling attention to divinities inside the “Backofen” (bread-baking oven). Heidegger asks

“is it concern for the monstrous and for one’s own goddess, one’s own [polis] when someone plays ‘dice’ with children in the goddess’s temple precinct?... Who is Artemis? It would be presumptuous to think we could answer this question through a few observations from mythology. The necessary and only possible answer here has the nature of a responsibility that contains the historical decision as to whether or not we are able to preserve the essence of this goddess...”[18]

Heraclitus is said here to offer a “characteristically obscure affirmation of the feminine realm.... [since] the domestic-feminine sphere... [as] distinct from the public-masculine sphere [shows] that the feminine is also divine.”[19] Heidegger’s veiled handling of Bachofen’s ‘prismatic’ but vastly ambiguous erudition also allows us to cut across and yet firmly delineate several antagonistic political, artistic and philosophical groupings. These antagonisms are, or may also be, emphasized and distinguished along economic, ideological and sensual lines regarding the property question. Nevertheless, David Pan argues against the “spurious view that fascist theories of myth advocated a return to mythic structures and the idea of myth is thus fascist ideological terrain.”[20] The simple fact that “patriarchy never found its female Bachofen,”[21] testifies to peculiarities within feminism and Marxism as separate concerns.

A few years after Marx had published The Civil War in France, and both he and Engels concluded their activity in the First International, Lewis Morgan published his now allegedly-surpassed anthropological work Ancient Society. Over this same period of the 1870s, labor movements acquired new proportions across the industrial world, and the seeds of what would become Bolshevik victory to bear fruit decades later were already being planted in the East. A particular tone of ‘radicalism’ in American reformist and ‘progressive’ politics also displayed many of the same features still apparent today. For Marxism in active theoretical becoming during the 1870s, it is Engels here who gives a description of its continuously edifying view of change standing on scientific legs, with Hegelianism,

“the history of mankind no longer appeared as a wild whirl of senseless deeds of violence, all equally condemnable at the judgment-seat of mature philosophic reason and which are best forgotten as quickly as possible, but as the process of evolution of man himself…”

Coupled with the most recent discoveries of scientific Materialism,

“new facts made imperative a new examination of all past history. Then it was seen that all past history, with the exception of its primitive stages, was the history of class struggles; that these warring classes of society are always the products of the modes of production and of exchange—in a word, of the economic conditions of their time. It was now the task of the intellect to follow the gradual march of this process through all its devious ways, and to trace out the inner law running through all its apparently accidental phenomena.”[22]

Habits and histories therefore are often easier to forget about than they are to be completely rid of.

L. Morgan’s own insights, in a manner not unlike Bachofen, also contributed problematic assertions for the ‘practice’ of academic or radical ‘Feminism’ more than a century later. In a seminal ‘Marxist-Feminist’ writing from the 1960s, M. Benston claims in a footnote,

“[m]odern anthropology disputes this [matriarchal] dominance but provides evidence for a more nearly equal position of women in the matrilineal societies used by Engels as examples. The arguments in this work of Engels do not require the former dominance of women but merely their former equality, and so the conclusions remain unchanged.”[23]

Which conclusions or changes are being proposed here? Today, there is both tentative movement and an apparently unshakable stagnation in cultural or gender theoretical discourse on the topic of historically dispelled ‘matriarchy.’ Different explanations since the 1960s have also been reached in archaeology and population studies investigating the Neolithic period. Moreover, Marx and Engels themselves had arrived at such topics from a still more considered approach. In addition to the unavoidable fact that many historically powerful working class fighters were born female, a predicted ‘restoration’ in history undertaken by the social revolution coheres as far more than logographic or quantitative signifier. Nevertheless, it was C. Fourier himself who observed as early as 1808 that “[i]n short, the extension of women’s privileges is the general principle of all social progress.”[24] The term ‘Feminism’ as understood in contemporary political context does not predate Marx or Marxism, though its coining is erroneously attributed to Fourier.[25] Could one at any time possibly become the other?

F. Engels in The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884), in addition to exploring other questions, establishes a kind of core thesis: Women’s oppression arose with class society. Over more than 2,500 years, developing relations of production and property in the Western European world transformed ancient kinship structures, steadily replacing aspects of remaining matriarchal systems (”mother-right”) with a private property-bound ‘patriarchal’ control to secure and pass on inheritance along the male line. Much ink and spleen are spewed in contesting this assertion as well. In either case, Western European processes of capital accumulation intensified the ongoing historical dissolution of long-standing family and village life and relegated average women to either dull domestic drudgery or industrial wage slavery or both. Engels was so grateful to the vast groundwork that Bachofen had laid, that he wrote to Kautsky in 1884 asking if the

“Old Bachofen”[26] would receive an inscribed copy of Engels’ new book. Second International Marxists such as C. Kelles-Krauz argued in the early 1900s that Bachofen’s research had been guided “by the ironic dialectic of history as if by a priestess of thought, [and] unearthed from beneath the layer of the bourgeois Renaissance the precious elements of a new, powerfully revolutionary Renaissance – the Renaissance of the communist spirit.”[27]

Kelles-Krauz also indicated that the ‘matriarchal’ lens of Bachofen provides a historical allowance enabling Marxists to analyze the “feminist aspect,”[28] at least from the perspective of development of the family and specific contemporary ‘survivals’ from that period. It has also been suggested that Walter Benjamin refers to Bachofen’s treatment of ‘matriarchy’ when drawing the reader to consider “mythical Mothers… a past that can be all the more spellbinding because it is not [one’s] own, not private,”[29] yet both for ‘primal’ and later matriarchal images of the past, “the fact that it is now forgotten does not mean that it does not extend into the present.”[30] Scholar Joseph Mali also argues that Benjamin attempted “to save Bachofen… from the clutches of German fascism,”[31] while Fromm claims that Bachofen’s matriarchal conjectures are “a sweeping and profound philosophy of history, in many ways similar to those of Hegel and particularly Marx.”[32] Benjamin adds however that this ‘myth’ becomes “blurred during those periods in which mothers themselves become agents of the class that risks the life of their sons for its commercial interests.”[33]

Engels forwards the claim that the:

“first class antithesis which appears in history coincides with the development of the antagonism between man and woman in monogamian marriage, and the first class oppression with that of the female sex by the male.”[34]

Compare this with Lewis Morgan, who writes that in ‘advancing’ from various stages of savagery to or beyond ‘barbarism’, these primitive “habits and modes of life divided the people socially into two great classes, male and female.”[35] Nevertheless, for the historically necessary extimacy and presumable bareknuckle inequality of such a foundational social arrangement, Marx and Engels assert the primitive household formation as being “naturally evolved” and “communistic”[36] rather than in all cases initially ‘antagonistic’ in essence. Importantly for all subsequent major debates in Western ‘radical’ discourse regarding ‘household labor,’ Marx also writes

“the evolution of products into commodities arises through exchange between different communities, not between the members of the same community. It holds not only for this primitive condition, but also for subsequent conditions, based on slavery and serfdom…”[37]

What occurred then that caused such ‘coincidental’ antagonisms between sexes to unfold, and to what extent were these apparently senseless causes forgotten or stricken from the record? Two years after Morgan’s Ancient Society had explored ‘survivals’ within this historical existence of a ‘mother-right’, August Bebel also claimed,

“with increasing division of labor there resulted not only a diversity of occupations, but a diversity of possessions as well. Fishing, hunting, cattle-breeding and agriculture, and the manufacture of tools and implements, necessitated special knowledge, and these became the special province of the men. Man took the lead along these lines of development and accordingly became master and owner of these new sources of wealth.”[38]

Bebel additionally tries to demonstrate that, “[a]s a result of this subjugation, woman came to be regarded as an inferior being and to be despised. The matriarchate implied communism and equality of all.”[39] If a matriarchate for Bebel also implies ‘equality of all,’ what has been contested by Benston and overturned by ‘modern day anthropology’ since the 1870s?

In Mesoamerica, West Eurasia and the far East, archaeological traces and findings gathered up to the present day may point to some form of ‘matriarchate’ thousands of years ago. At Çatalhöyük, in present day Turkey, recently discovered matriarchal or matrilineal DNA patterns and woman-focused grave goods distribution suggest that

“7th millennium B.C…. social organisation and symbolism stand in stark contrast with the predominantly male-focused societies that emerged in West Eurasia in subsequent millennia.”[40]

The earliest known examples of woven textiles[41] also come from Çatalhöyük. In ancient Persia,

“Women were in charge of cooking, making earthen ware, as well as looking after the fire, their children and their homes. They were also in charge of tribal affairs. Family relations followed the female line…. Not only women held positions of economic and social leadership, but were solely in charge of the spiritual affairs of their tribes.”[42]

In each case, women’s relatively heavy labor burden in this respect undoubtedly was seen as being in direct connection with and a complement to their important social standing. In Neolithic China, a site at “Fujia” associated with the Dawenkou culture reveals a high probability of matrilineal descent which may “suggest that its social dynamics resemble those of modern matrilineal societies with a lower degree of heritable resources and private properties.”[43] Mesoamerican recollections associated higher female social status directly to participation in the production of textiles. For instance, a young Nahua woman would be told: “It is not your destiny, it is not your fate, to offer [for sale] in people’s doorways, greens, firewood, strings of chiles, slabs of rock salt, for you are a noblewoman. [Thus], see to the spindle, the batten.”[44]

Perhaps as an exception in the ancient non-Greek world, Abrahamic traditions highlight a development of class and inheritance alongside a higher labor-centered status for women. Bebel claims that in the ancient past,

“Mosaic law [was] framed in a manner destined to prevent the Jews from developing beyond the stage of an agricultural society, because their lawmakers feared that it might bring about the downfall of their democratic, communistic organization... For the same reasons, moreover, the Jews were kept at a distance from the sea, which is favorable to commerce, colonization and the acquirement of wealth.”[45]

Elsewhere, Bebel states “The Jews are the sworn enemies of Malthusianism.”[46] But for various distinctions between family or village and the development of individual property on this point, Lafargue argues “[a]mong the Jews and Semitic peoples there was no private property in land,”[47] or else he and Bebel do not appear to disagree here.

Lafargue in 1886 wrote that

“[c]ivilization often works against nature, making pregnancy difficult, childbirth laborious and painful, and suckling dangerous, often impossible: thus, it weakens maternal love in women. The savage woman loves her child above all else; she nurses it for two years, never hitting it; the child, which the mother protects from the brutalities of men, clings to her, as chicks flee beneath the wings of a hen at the slightest danger. Woman, therefore, was destined by nature to carry the totem of the clan.”[48]

So both the cult of woman and the cult of nature alternatively have taken on various meanings and been supplanted as a consequence of different modes of human economic practical development or development of the family rather than the other way around. Lafargue points out that still in the Basque culture, “[t]he husband… is his wife’s head servant.”[49] Is this also the ‘equality’ implied later by Benston? Marx and Engels go into some detail on this development of woman’s subjugation having taken on a peculiar intensity in Western Europe, yet elsewhere:

[T]he unity can extend to the communality of labor itself, which can be a formal system, as in Mexico, Peru especially, among the ancient Celts, and some Indian tribes. Furthermore, the communality within the tribal system can appear more like the unity being represented by a head of the tribal family or as the relationship between the fathers of the family. This then leads to either a more despotic or democratic form of this community. The communal conditions of actual appropriation through labor, water pipes (very important among Asian peoples), means of communication, etc., then appear as the work of the higher unity.[50]

Peoples whose women have to work much harder than we would consider proper often have far more real respect for women than our Europeans have for theirs. The social status of the lady of civilisation, surrounded by sham homage and estranged from all real work, is infinitely lower than that of the hard-working woman of barbarism, who was regarded among her people as a real lady (LADY, frowa, Frau=mistress) and was such by the nature of her position.[51]

For Marxists then, the primitive communist household is said to have prevailed where the division of labor between sexes emerged out of a long and difficult “natural” process. Bachofen describes the transition from a “telluric” age of ‘hetaerism’ to a form of primeval Communism which “even seemed to him inseparable from gynecocracy.”[52] Such a transition can be seen to have already taken place through a usefully abstract example given by Marx,

“the women of the family spinning and the men weaving, say for the requirements of the family – yarn and linen were social products, and spinning and weaving social labour within the framework of the family.”[53]

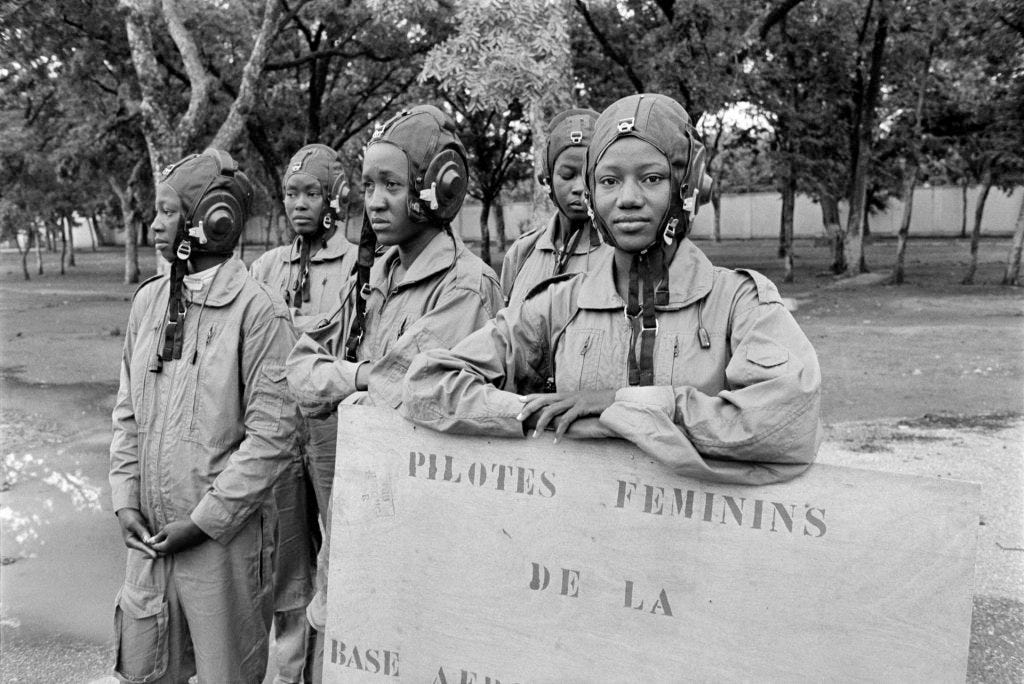

To this extent, a ‘natural’ division of labor exists between, but not within, the sexes. Stalin himself wrote in 1906 of that time long ago “under the matriarchate, when women were regarded as the masters of production.”[54] The WWII ‘Night Witch’ female aviator M. Raskova recounts once when

“Comrade Stalin took the floor. He spoke quietly, but so clearly that everyone could hear him. He spoke simply and with remarkable wit. He recalled the time of matriarchy, explained what matriarchy was, how it came about that women were more thrifty than men, that women began to cultivate crops while men only hunted, and that women turned out to be more important than men. Then he spoke of the plight of women throughout the centuries that followed. He talks about how women were oppressed, deprived of their rights to a simple human existence.”[55]

The period being referred to here is not yet the period in which man has become ‘bourgeois’ and woman ‘proletarian.’

A view of ancient China as containing such a primeval communistic form in historical practice was pointed out by Marx himself where he notes, “this communism, based on natural growth (although itself formed through a long historical process), was also the original form in China can be seen, for example, in Abel, etc.”[56] Alternatively, the rise of a Greek gens and forms of patriarchal private property saw an almost complete reversal of these once integrally wefted communal ‘circles’ of unity between manufacturing and agriculture. A glaring example of such historical rupture also appears in reconfigurations of the myth of Athena by which Lafargue shows these tropes being originally adapted to “a savage tribe, war loving and ferocious, who sent colonies from Africa to Greece and Asia Minor.”[57] Lafargue argues that myths themselves both transmit and ‘forget’ the old, all while retaining suggestions of the obvious. In Roman myth too, “Jupiter carried off Metis to assimilate her cunning, her prudence and her wisdom, for her name in the Greek language has these diverse meanings.”[58] He continues:

The epithet Tritogeneia meant that Athena was thrice-born – for she belonged originally to the group of antique self-born goddesses – but, in the course of time, when her savage adorers reached the stage of development in which the matriarchal family was constituted, she was endowed with a mother, who bore different names, according to the people who worshipped Athena; and at last, when on earth, and afterwards in heaven, man had become the ruling power in the family, she consented, to the great joy of the gods, to recognise the authority of Zeus, who went through the ludicrous ceremony of giving her birth[59]

Lafargue’s treatment of the ‘myth’ of Adam and Eve also examines essentially economic questions, stating that moderns must first see that

“[m]yths are neither inventions of deceivers nor idle fantasies; they are rather one of the most naive and spontaneous forms of human existence. Only then will we come to know the childhood of humanity when we are able to unravel the meaning they had for primitive people.”[60]

Bebel observes “the ancient cults continued to dominate the minds for centuries; only their deeper meaning was gradually lost.”[61] For these late 19th century able-bodied Western European cis-heterosexual males’ sake, if ‘matriarchal’ historical assumptions were passed down merely as a patchwork of myths, Pomeroy admits how “we are haunted by the question of whether women could have participated in their creation.”[62] What about in the creation of class antagonism itself? These blatant degradations of ‘hetaerism,’ as Engels shows, later transformed “to monogamy… brought about essentially by the women.”[63] Only after the shifting from a homogenizing polyamory and ‘group marriage’ to pairing, family “had been affected by the women could the men introduce strict monogamy.”[64] Or rather, monogamous restrictions that only applied to women. Somewhere between asserting ‘goddess’ worship as grounds either for subjugation or ‘veneration’ and identifying a nearly forgotten labor-centered high status for women in the archaeological record, Paul Lafargue’s insights do resemble Thomas Sankara’s:

The superior position in the family and society, which man conquered by brute force, at the same time as it forced him into a cerebral activity to which he was little accustomed, placed at his disposal means of intellectual development, constantly increasing. The woman, tamed, according to the Greek expression, enclosed in the narrow circle of the family, from which direction was taken away, and having little or no contact with the outside world, saw on the contrary the means of development which she had enjoyed reduced to almost nothing and to complete her enslavement she was forbidden the intellectual culture given to man. If… the female brain continued to evolve, it is because the intelligence of the woman benefited from the progress made by the male brain; for one sex transmits to the other the qualities which it has acquired[65]

What then were the immediate or more general causes of matriarchy’s overthrow in the materialist sense? Lafargue here gives two seemingly contradictory reasons:

Unquestionably it was the desire to shake off this feminine ascendancy and to satisfy this feeling of animosity which led man to wrest from woman the control of the family[66]

Collective property, if not the sole cause, was, at all events, the pre-eminent cause of the overthrow of the matriarchate by the patriarchate[67]

Is collective property therefore some hyper-masculine dissident ‘feeling of animosity?’ Is the socialist revolution, or ‘progress,’ merely a relict of man’s undifferentiated and unchanging or ineffably gender-based desire to ‘overthrow’ matriarchy? This is unlikely, although there is power in the assertion made that with the rise of slavery and animal husbandry, there would also develop both private property and a ‘royal’ womanhood. What was customarily household labor for household consumption became also a warped and senseless self in Western Europe, since “the ceaseless weaving acquires a magical quality, as though the women were designing the fate of men.”[68] According to Lafargue, “Man… was thus obliged to begin deifying woman… ‘Zeus himself can not escape destiny,” but eventually, “the idea that woman had no soul became so rooted so firmly in the ancient world…”[69] that a change to worship of a household patriarch and feeding of the dead also persisted into early Christianity. Although Lafargue asserts St. Augustine justified this saying “the faithful carried food to the tombs of the martyrs, but he adds that they ate it on the spot or distributed it to the poor.”[70] To this extent, it is also argued by one ‘marxist’-Feminist that it’s no accident “Mary’s cult as Theotokos… was established at… Ephesus, the site of… the temple of Artemis… like Mary, both a virgin and a great mother.”[71] Bachofen also claims “[v]irginity and motherhood are closely connected, while hetaerism denies both.”[72]

Bebel puts forward several arguments suggesting that the development of “Iron tools”[73] or fishing and domestication of animals also accelerated and multiplied this factor of force and overthrowing of ‘mother-right.’ Soviet anthropological studies suggested that in ‘barbaric’ societies beyond the historical frontier of Western and Greek societies such as

“[a]mong the Scythians, women participate in war on an equal basis with men, not inferior to them in courage, and in certain eras the bravest women stood at the head of government among this people. Among the Ethiopians, women bear arms and are obliged to serve in the army for a certain period. Finally, even among the Gauls, women compete in courage with men Pomponius Mela (1st century) reports that among the Ixamat women do the same as men, and are not even free from military service; the men of this people fight on foot and shoot from a bow, the women are on horseback, but do not use weapons, but lassos, with which they strangle enemies, and until they kill the enemy, they retain their virginity.”[74]

Indispensable if easily forgotten, a “critical knowledge of the evolution of the idea of property,”[75] and its resulting societal or communal questions must be posed over this or that specific perspective or individually traumatic manifestation. Soviet scholar Mark Kosven in the late 1940s wrote that while

“[h]umanity also has its own constant, organic, universal path of development. At the same time, we are far from affirming a unilinear, uniform evolutionary development of all peoples… [and matriarchy] turns out to be distinct and unique in each individual society.”[76]

To what forces did these various kinds of ‘matriarchate’ ultimately succumb in history? In short, the movement from ‘hordes’ to clan and village life involved the movement into a technologically primitive form of Communism that itself at various times resulted in a geographical sprawl and perhaps to varying degrees the “slave trades facilitated the adoption of matrilineal kinship.”[77] Kosven also mentions the many interweaving and overlapping processes whereby “[m]atriarchy, disintegrating and transitioning to patriarchy, leaves behind a number of relics, representing changing, dying elements of the forms and relationships that existed in full force under matriarchy.”[78] This too eventually led to a paternal kinship alongside and then again to the exclusion of ‘mother-right.’ Marx here argues that,

“[i]t is impossible to overestimate the influence of property in the civilization of mankind. It was the power that brought the Aryan and Semitic nations out of barbarism into civilization.”[79]

Woman’s pre-eminence in the ancient gens and clan or within these middle and ‘upper stages of barbarism’ must also have come with a proposition. The receding forests and transition to settled agriculture brought along vast changes in the division of labor. ‘Surplus production’ outside the family/village, though still miniscule in comparison to the age of industrial capitalism, led also to a ‘surplus’ of domesticity in each ‘ascending’ phase of civilization. Engels charges that we presently “know nothing as to how and when this revolution was effected among the civilised peoples. It falls entirely within prehistoric times.”[80] Though it is obvious that to exchange ‘something’ for nothing then was among the listed prices of avoiding manual labor and winning the chance to become a “superintendent of female slaves”[81] in the emerging changes to the prevailing order. In Ancient Greece, this reached ridiculous and debauched proportions, “that one had first to become a [‘reputable’ prostitute] in order to become a woman is the strongest indictment of the Athenian family.”[82] Eventually, Marx claims, women’s inculcated inferiority “came to be accepted as a fact by the women themselves.”[83] Olive Schreiner, at one-time a close friend of Marx’s daughter Eleanor, rather unceremoniously deems this kind of degradation as “sex-parasitism.”[84] Arguing that, as use of metal tool-making, beasts of burden, settled agriculture and private property all expanded and lowered the socially-required labor time for certain strata,

“the need for [female] physical labor having gone, and mental industry not having taken its place, [woman] bedecked and scented her person, or had it bedecked and scented for her, she lay upon her sofa, or drove or was carried out in her vehicle, and, loaded with jewels, she sought by dissipations and amusements to fill up the inordinate blank left by the lack of productive activity.”[85]

Marx insists that

“Struggle for… Possession of the most desirable territories, localization of tribes in fixed areas, vu. in fortified cities, with… increase the population. Advanced martial arts.... These changes indicate the approach of civilization.”[86]

Idleness alongside ‘veneration’ may have been mythically consensual for one group or one generation, but the control of slaves, or control of alluvial plains and granaries, long-distance trading routes, waterworks and underdeveloped forms of manufacture themselves all break down and reassert themselves upon corresponding changes in relations of production and social dislocations in wealth’s movability/fixity. This also becomes the “control” and sale of women, just as much as it may have once involved women also participating in the maintenance of communal property for many generations prior. Expansion of production among the prehistoric Greeks and Roman gens must also, at some point, have produced a metal-working and highly disruptive contingent among the barbaric ‘outcasts’ as well. Morgan quotes a missionary’s description of the American Seneca’s tribal lifeways:

“[t]he stores were in common; but woe to the luckless husband or lover who was too shiftless to do his share of the providing… he might at any time be ordered to pick up his blanket, and budge… The house would be too hot for him… The original nomination of the chiefs always rested with [women].”[87]

Woman was a slave, and woman controlled slaves. Man was a slave, and man controlled slaves. Iron smelting and domestication of large beasts of burden however are what those groups such as the Iroquois lacked. One may reasonably infer that among geographical areas where metal tool-making and animal husbandry, coupled with this expansion of a ‘kóryos’ of socially outcast youth roving the countryside, a growing risk of ‘barbarity’ outside, or ‘sex-parasitism’ within the polity, could only be kept at bay at the expense of ‘communal life.’ In Europe, this meant the end of locally maintained stores or pastures in common and the formation of patriarchal inheritance both of land and the labor needed to work it. Marx explains:

For now slavery too had been invented. The slave was of no value to the barbarian of the lower stage. It was for this reason that the American Indians treated their vanquished foes quite differently from the way they were treated in the upper stage. The men were either killed or adopted as brothers by the tribe of the victors. The women were either taken in marriage or likewise just adopted along with their surviving children. Human labour power at this stage yielded no noticeable surplus as yet over the cost of its maintenance. With the introduction of cattle breeding, of metalworking, of weaving and, finally, of field cultivation, this changed. Just as the once so easily obtainable wives had now acquired an exchange value and were bought, so it happened with labour power, especially after the herds had finally been converted into family possessions. The family did not multiply as rapidly as the cattle. More people were required to mind them; the captives taken in war were useful for just this purpose, and, furthermore, they could be bred like the cattle themselves[88]

Lafargue continues to say that:

So it may be said that humanity, since it emerged from communism of the clan to live under the system of private property, has been developed by the efforts of one sex alone and that its evolution has been retarded through the obstacles interposed by the other sex. Man by systematically depriving woman of the means of development, material and intellectual, has made of her a force retarding human progress... this has been retarded ever since humanity entered into the period of civilization and private property, because then woman, constrained and confined in her development, cannot contribute to it in so effective a way[89]

Bebel deems this more or less rapid change from different kinds of clan and communal property to patriarchal private property as the West’s “first great revolution.”[90] Engels also explains this was the:

[F]irst form of the family to be based, not on natural, but on economic conditions – on the victory of private property over primitive, naturally developed common ownership… Monogamous marriage was a great historical advance; nevertheless, together with slavery and private wealth, it opens the period that has lasted until today in which every step forward is also relatively a step backward, in which prosperity and development for some is won through the misery and frustration of others[91]

Engels further demonstrates that the mistreatment by Telemachus[92] of his own mother exemplifies this close association between women and textile production/unraveling so central to the Odyssey’s plot, as well as the insistence in Greek civilization upon man’s domination over women. For present day anthropology and for Marxists looking back on ancient history, though evidence may often be seen that deigns

“to assert the presence of male dominance, it is always much more difficult to define its precise degree, and equally difficult to affirm its total absence. The point is not even that, for primitive societies, sex equality – in the rigorous sense of the term, that of the disappearance of gender – was an unachievable ideal: it could not be, and never was, an ideal at all. Pre-capitalist peoples did not necessarily establish an explicit hierarchy between the sexes; the idea of the superiority of one sex over the other… while it exists in most cultures, is by no means universal. In a number of societies, the sexes are not conceived in terms of different values, and this does not prevent men from having rights that women are denied.”[93]

How then might a recovery of such history also assist us to throw on the habiliments needed to cover a hypermodern unadorned and unfilial shame? An obverse approach to these ‘survivals’ in the Russian context of communal agriculture was once highlighted by Engels when he said that the ‘Obschina’ must be looked at from a perspective “other than the Western one.”[94] But whether from within or outside such bounds, a ‘forgetting’ has already filled this gap. Walter Benjamin, turns this part of the drama toward a more monistic object:

[T]he Penelope work of recollection. Or should one call it, rather, a Penelope work of forgetting? Is not the involuntary recollection, Proust’s memoire involontaire, much closer to forgetting than what is usually called memory? And is not this work of spontaneous recollection, in which remembrance is the woof and forgetting the warf, a counterpart to Penelope’s work rather than its likeness? For here the day unravels what the night was woven. When we awake each morning, we hold in our hands, usually weakly and loosely, but a few fringes of the tapestry of lived life, as loomed for us by forgetting. However, with our purposeful activity and, even more, our purposive remembering each day unravels the web and the ornaments of forgetting[95]

Proto-‘Feminism’ and the Woman’s Industrial Revolution

altho The air of Paradise did fan the house,And Angels offic’d all; I will be gone[96]

From Medieval ‘querrelle des femmes’ polemics to the many treatises written since the European Renaissance, we recall that educated, or non-working, women in the West also had an early hand in forwarding their particular class’ ‘noble’ views on Women’s Rights. Some men too, such as Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa in the early 1500s, tried to demonstrate that due to the fact Eve had been made within the walls of Paradise and after Adam, woman was the superior sex. This despite a “tyranny of men”[97] placed upon her. Highly placed women therefore contributed early on to the cultural patterns of Women’s Rights movements to come. These women were not universally silenced, although many were made to forego the use of their husbands’ & fathers’ names in publishing things like:

That we are more witty [than men] which comes by nature, it connot better be proved, than that by our answers, men are often driven to Non plus[98] – Jane Anger

This is our Case; for Men being sensible as well of the Abilities of Mind in our Sex… began to grow Jealous, that we, who in the Infancy of the World were their Equals and Partners in Dominion, might in process of Time, by Subtlety and Stratagem, become their Superiours; and therefore began in good time to make use of Force (the Origine of Power) to compell us to a Subjection, Nature never meant; and made use of Natures liberality to them to take the benefit of her kindness from us[99] – a Lady

[W]ere the Men Philosophers in the strict sense of the term, they would be able to see that nature invincibly proves a perfect equality in our sex with their own[100] – Sophia, a person of quality

These and similar questions in their abstract form persisted, with much of the immediate post-1789 movements around women’s equality, particularly in France, reflecting similarly bombastic notions. In 1793, the Marquis de Sade had commented harshly on the female assassin of Marat. Charlotte Corday had been incensed by what she saw as revolutionary ‘excesses’ and stabbed Marat to death while he was bathing. Sade excoriates her as “like those mixed beings to whom no sex can be assigned, vomited by hell for the despair of both, does not belong directly to any... a Tartar fury.”[101] This dehumanized archetype of a ‘femme-homme’ would continue to inspire discomfort. A later example, though just as jarring, is that of the Saint-Simonians and Simon Ganneau, a mystic and charismatic rabble-rouser who tried to embody ‘androgyne’ characteristics. Saint-Simon’s successors claimed that a “Female Messiah”[102] would be found in the ‘Orient’ and several followers set out to try and find her. As a direct influence upon people like Flora Tristan, charismatics such as Saint-Simon, Ganneau and their many followers attempted to combine this feminine fervor with utopian spiritualist constructions. One acolyte asserted:

MY TEMPLE IS A WOMAN[103]

It is not for nothing then that the first recorded political usage of the term “feminists,” [104] as a pejorative referring to equal-rights activists, was by A. Dumas, a one-time follower of Ganneau. In 1840s America, middle-class women writers could see more Earth-bound ‘bread & butter’ issues of the day and reflect upon them, but to what political end?

[V]isions of the past crowded upon me… our merry-makings and our tragedies, my school-mates, the partners of my life, the partners of my hoped-for immortality… My binding tears fell thick and heavy… Lilly [a Freedwoman domestic worker, wiped the tears]… and rolling up the quilt thrust it back into the old cupboard… As I retraced my way to the village I marked the changes since this patchwork history was constructed. The Indians that figured in Queen Anne’s broadcloths… driven from their loved homes… into the shadowy West and are melted away. The wooded sides of our mountains have been cleared to feed yonder smoking furnace. Those huge fabrics for… chemical experiments indicate discoveries in science that have changed the aspect of the world… Houses have decayed and new ones have been built over the old hearthstone… Families have multiplied and sent forth members to join the grand procession… at this very moment the bell is ringing for a meeting of the town to extend the limits of our burying-ground, it being full! All these changes and the patch-work-quilt remains in its first gloss![105]

What is decisive in the stitching together and creation of history, as well as the creation of man, is “purposive activity” and not a theorized and reflexively sorrowful or mystified sense of resignation. It is labor and technological change which decisively intervene and disclose man’s relationship to Nature. Here, Lafargue gives credence to modern society that “until the epoch of the great mechanical industry, trades were mysteries, whose practices were professional secrets, jealousy hidden from the profane and revealed only to the initiated… crafts of artisan manufacturing, where manual skill and knowledge play a preponderant part, have contributed to reinforce… the human toward religious mysticism.”[106] This must also apply to the textile industry. It is just this type of large-scale mechanized industrial labor offering and requiring that the workers be put under pressure and form new ways of communal being, as well as to discard the obscurant ‘craft’ esotericism. Though luminescent aspects of ancient ‘myths’ also linger, it was the inhumane rise of capital’s anarchic and disruptive rule that subjugated men and women in the working classes, not their specific belief systems or romantic failures interpersonally. Engels shows that it is the economic condition of modern society: “which unsexes the man and takes from the woman all womanliness without being able to bestow upon the man true womanliness, or the woman true manliness -- this condition which degrades, in the most shameful way, both sexes, and, through them, Humanity”[107] Bebel offers encouragement here:

No movement of great importance has ever taken place in the world, in the past or present, in which women have not played a prominent part as combatants and martyrs[108]

Marx and Engels showed[109] that the year 1825 marks capitalism’s first great general crisis. Coincidentally, 1825 was also the first substantial U.S. women’s industrial labor organizing effort and rallying for wage increases.[110] Were working men simply trying to silence these female working class fighters and prevent them from speaking for their class interests? In the year:

“1831, during the tailoresses’ strike, “A Mechanic” repeatedly urged the women on, suggesting that they open their own shop and receive work based on their own pricelist… [w]hen the women shoe binders organized in 1835, one union member offered a detailed exposé of the atrocious conditions in which the women labored and concluded that “it is high time, in this republic, that such slavery is done away with.” The all-male shoe binders’ union agreed and passed a strong resolution of support… [the New York Association of Journey Bookbinders] approved a public address expressing its deep interest in the women’s struggle and vowing to use ‘all honorable means’ to help them… the National Trades’ union went so far as to suggest that all trades affected by female labor add women’s auxiliaries to their unions”[111]

For enslaved women in America at the same time, ‘family life’ was itself a cruel and torturous experience completely predicated on violently enforced property claims and involuntary lifelong domestic servitude. Harriet Jacobs was not only harassed and abused by her former master who threatened to sell off her children if she didn’t comply, but in her prolonged escape, she had to hide underneath the floorboards of a nearby house for almost a decade. Intentionally deforming herself to avoid what were the master’s constitutionally-upheld property claims against her life. In one incident, Jacobs swore she heard her former master coming to eject her from the crawlspace. But she remained hidden, “the key was turned in my door… and there stood my kind benefactress alone… ‘I thought you would hear your master’s voice’ she said… ‘I came to tell you there is nothing to fear. You may even indulge in a laugh at the old gentleman’s expense. He is so sure you are in New York… The doctor will merely lighten his pocket hunting after the bird he has left behind.’”[112] Mary Livermore claimed to have spoken to a slave ‘Aunt Aggy’ who told Mary that before the Civil War she had prayed for the Lord to “hasten de day when de blows, an de’ bruises, an’ de aches, an ‘ de pains , shall come to de white folks , an’de buzzards shall eat’em as dey’s dead in de streets. Oh, Lor’ ! roll on de chariots , an ‘ gib de black people rest an ‘ peace.”[113] Her prediction came true. Nevertheless, many ‘feminist’ leaders of the time in America such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton still could only exhibit fear of immigrants and laboring “lower orders of foreigners”[114] like Irishmen or Black men or Germans or Asians, who after obtaining some measure of formal equality, would rule alongside Anglo-Saxon men and crowd ‘noblewomen’ such as Stanton out.

The labor organizer Sarah Bagley fought for a reduction in work hours, whereas more refined ‘thinking women’ like Harriet Farley pressed for upwardly mobile demands of ‘respectability’ in the 1830s and 1840s. Between the two of them, the feminine “mind among the spindles”[115] being referred to in their heated debates apparently took on a different character. Textile mill owners themselves, who saw Farley’s positive portrayal of ‘emancipatory’ aspects of industrial working life for women as a valuable advertisement for employment in their mills “bought back subscriptions and supplemented the pay of the editors. The mill owners’ support undermined the paper’s reputation among mill women, and the paper folded in 1845.”[116] On the other hand, Bagley’s working class fervor also failed “to gain respect from middle-class women,”[117] who were themselves more well-placed in reformist social movements. Sarah Bagley also polemicized with the Abolitionist William Garrison, who had come out against the labor unions. Bagley asked “[d]o our anti-slavery friends over discuss the merits of the Labor question?… We discuss all of these, and Slavery, South and North… What say, friend, Garrison? …Affinities find each other, say you, and we shall understand each other in due time. Till then let us exercise charity for each other, and not claim for ourselves more of the genuine spirit of reform, than we are willing to award others, who are laboring as sincerely as ourselves, if not in the same department, in some other, to bring about the glorious era, when wrong and injustice shall cease, and universal rights shall be recognized from East to West, from North to South.”[118] Lacking the scientific orientation and partisan spirit that subsequent decades would grant to the workers’ movement, zig-zags “(or the female line, as certain wits [call it]… not without reason)”[119] in organizational methods were still being made, though perhaps not abstractly as regards ‘feminism.’ During the uproarious 1840s, Flora Tristan had also taken up the struggle of working people:

Workers, you are unhappy. Yes, no doubt; but where does the main cause of your ills come from?... If a bee and an ant, instead of working in concert with the other bees and ants to supply the home commune to live, they were advised to separate and want to work alone, they too would die of cold and hunger in their solitary corner. Why then do you remain in isolation?... —Isolated, you are weak and fall overwhelmed under the weight of miseries of all kinds! — Well then! Come out of your isolation: unite! — Union is strength[120]

Tristan in Europe and in her travels, though still anti-slavery, was however not as racially[121] enlightened as Bagley or others, and also did not forward class struggle as such. A year after Flora Tristan addressed these crowds of angry workers, the ‘anarchistic’ and anal-retentive radical set in Germany fired back at her, but Marx and Engels appear to defend Flora’s role, if only to highlight what she forgot:

The worker creates even man; the critic will never be anything but sub-human though on the other hand, of course, he has the satisfaction of being a Critical critic.

“Flora Tristan is an example of the feminine dogmatism which must have a formula and constructs it out of the categories of what exists.” Criticism does nothing but “construct formulae out of the categories of what exists”… Formulae, nothing but formulae. And despite all its invectives against dogmatism, it condemns itself to dogmatism and even to feminine dogmatism. It is and remains an old woman — faded, widowed Hegelian philosophy which paints and adorns its body, shrivelled into the most repulsive abstraction, and ogles all over Germany in search of a wooer[122]

Marx and Engels are not rejecting women in the revolutionary and labor movements so much as feminist and ‘anti-feminist’ posturing at the level of ‘criticism’ from abstract moral principle, or the mere lack thereof. The individual’s memory is not the primary arena of class struggle, neither then is the emotionally individuated rehashing of such critically ‘lived experiences.’ Benjamin also writes that “what has been forgotten... is never solely individual… Everything forgotten mingles with what has been forgotten of the prehistoric.”[123] The social metabolic process of material production is this primary arena of revolutionary undertaking, whether today or 15,000 years ago. Women and children ripped out of their homes in the endless search for wages not only disrupts domestic situations undergoing various states of ‘tranquility’ or ‘strife,’ it pits men already in competition among themselves as now competing for wages directly against their very own families:

Thus the social order makes family life almost impossible for the worker… The husband works the whole day through, perhaps the wife also and the elder children, all in different places; they meet night and morning only, all under perpetual temptation to drink; what family life is possible under such conditions? Yet the working-man cannot escape from the family, must live in the family, and the consequence is a perpetual succession of family troubles, domestic quarrels most demoralizing for parents and children alike[124]

Engels extends this to say “[i]f the family of our present society is being thus dissolved, this dissolution merely shows that, at bottom, the binding tie of this family was not family affection, but private interest lurking under the cloak of a pretended community of possessions.”[125] Some few decades later, with the major strife of the American Civil War behind them and a resulting rise of the organized industrial labor movements in the U.S., it was not lost on that generation at all that working class concerns would also have to take on a more partisan path for both sexes. William Sylvis did not silence women laborers either, comparing one’s misery to another:

As men struggling to maintain an equitable standard of wages and to dignify labor, we owe it to consistency, if not to humanity, to guard and protect the rights of female labor, as well as those of our own. How can we hope to reach that social elevation for which we all aim, without making woman the companion of our advancement as she has been of our depression? Are we to march on to the goal of our ambition and leave her behind to drink the dregs of misery?[126]

Marx took note of this ‘sensitive’ approach and commended the “very great progress… demonstrated at the last congress of the American ‘Labor Union’, inter alia, by the fact that it treated the women workers with full parity; by contrast, the English, and to an even greater extent the gallant French, are displaying a marked narrowness of spirit in this respect.”[127] In Russia during the late 19th and early 20th centuries too, the momentous wheels of change and the brutal processes of historical development lurched ever forward and people like V. Zasulich and K. Zetkin and A. Kollontai could not but observe a similar reality unfolding under brutal early capitalistic conditions in Russia:

However, the working class knows who is to blame for these unfortunate conditions. The woman worker, no less than her brother in suffering, loathes that insatiable monster with the gilded maw which falls upon man, woman and child with equal voracity in order to suck them dry and grow fat at the cost of millions of human lives. The woman worker is bound to her male comrade worker by a thousand invisible threads, whereas the aims of the bourgeois woman appear to her to be alien and incomprehensible, can bring no comfort to her suffering proletarian soul and do not offer women that bright future on which the whole of exploited humanity has fixed its hopes and aspirations. While the feminists, arguing the need for women’s unity, stretch out their hands to their younger working-class sisters, these ‘ungrateful creatures’ glance mistrustfully at their distant and alien female comrades and gather more closely around the purely proletarian organisations that are more comprehensible to them, and nearer and dearer to their hearts[128]

It is against such a background that a political vanguard of working class revolutionary transformation takes shape in the early proletarian socialist movement. This too is stalked by the same nagging attempts to waylay that development in a series of counter-posed turns shouting for ‘unity.’

[C]an man or woman choose duties? No more than they can choose their birthplace or their father and mother[129]

Heroines and Harpies

What is the aim of the feminists? Their aim is to achieve the same advantages, the same power, the same rights within capitalist society as those possessed now by their husbands, fathers and brothers. What is the aim of the women workers? Their aim is to abolish all privileges deriving from birth or wealth. For the woman worker it is a matter of indifference who is the ‘master –a man or a Woman. Together with the whole of her class, she can ease her position as a worker[130]

The modern industrial system has changed the ‘little shop of the primitive patriarchal master into the large factory of the Bourgeois — capitalist. Masses of operatives are brought together in one establishment, and organised like a regiment of soldiers ; they are placed under the superintendence of a complete hierarchy of officers and subofficers. They are not only the slaves of the whole middle-class (as a body,) of the Bourgeois political regime, — they are the daily and hourly slaves of the machinery, of the foreman, of each individual manufacturing Bourgeois. This despotism is the more hateful, contemptible, and aggravating, because gain is openly proclaimed to be its only -object and aim. In proportion as labour requires less physical force and less dexterity — that is, in proportion to the development of the modern industrial system —-is the substitution of the labour of women and children for that of men. The distinctions of sex and age have no social meaning for the Proletarian class. Proletarians are merely so many instruments which cost more or less. When the using-up of the operative has been so far accomplished by the mill-owner that the former has got his wages, the rest of the Bourgeoisie, householders, shopkeepers, pawnbrokers, etc., fall upon him like so many harpies[131]

Women in the 19th century labor movement ran a double risk of being both silenced and forgotten, but did this keep them from contributing to early Marxist and proletarian socialist history? In the passage directly above, a quoted section of The Communist Manifesto is presented in its first English translation from 1850. Helen Macfarlane here includes this key line regarding women and children’s wage labor and the ‘social meaning’ of sex distinctions disappearing as a result. In Russia too, the developments of Western Europe were brought by both force and accident. By the late 1860s, Elisabeth Dmitrieva had read Chernyshevsky’s What is to be Done and was inspired to follow the novel’s main character Vera Pavlovna in pursuing a ‘marriage-of-convenience’ as her springboard into the general revolutionary ferment. Dmitrieva emigrated while still a teenager to Switzerland and then later met Karl Marx in England. After growing quite close to Marx’s daughters, Dmitrieva was tasked by Marx to travel to Paris as a representative of the First International and went on to achieve much in just a few months’ time. The fighting and losses in Paris gave some hope as “after the heroic struggle of women workers on the barricades, their international prestige had grown significantly. For the first time, the revolution brought to the arena of struggle not individuals, but masses of women.”[132] So it was that “the very dream that Elizaveta Dmitrieva had begun to realize during the days of the Commune was realized: the women’s movement merged with the international movement of the proletariat.”[133] Dmitrieva’s jointly published address written as one of the leaders in the “Women’s Union” during the Commune’s fiercest period of fighting attests to this determination:

[I]t is not peace, but all-out war that the workers of Paris have come to demand! The tree of liberty grows watered by the blood of its enemies... All united and resolute, grown and enlightened by the suffering that social crises always bring in their wake, profoundly convinced that the Commune, representative of the international and revolutionary principles of the peoples, carries within it the seeds of the social revolution, the women of Paris will prove to France and to the world that they too will know, at the moment of supreme danger, at the barricades, on the ramparts of Paris, if the reaction forces the gates, how to give like their brothers, their blood and their lives for the defense and triumph of the Commune, that is to say, of the people! Then, victorious, able to unite and agree on their common interests, workers, all in solidarity, will, by a final effort, forever annihilate every vestige of exploitation and exploiters![134]

So disruptive were these images and developments of the working women doing battle for the Paris Commune’s defense that tropes emerged caricaturing these women as ‘petroleuses’ [arsonist women] who by “forgetting their sex and their gentleness to commit assassination… to burn and to slay; little children converted into demons of destruction, and dropping petroleum into the areas of houses… all combine to enact on civilized ground… scenes which find a parallel only in the infernal regions imagined by prophets and poets.”[135] Marx’s own daughters also underwent somewhat less harrowing experiences during the ‘Commune’ on the French border with Spain. Engels commented that when Lafargue and the Marx girls attempted to cross from France into Spain, they were arrested and nearly-incriminated as Jenny carried a letter from a commander of the Commune that she quickly stashed away in “a dusty old account book.”[136] The Marx girls’ subsequent answers so frustrated the French police that they stormed out of the interrogation room muttering “in a fit of rage about ‘the energy that seems peculiar to the women of this family.’”[137] Jenny later wrote in Victoria Woodhull’s magazine that her sister and Lafargue’s personal plight was not the focus, and from this the reader should “[t]hink only of the ‘petroleuses’ before the court-martial of Versailles, and of the women who, for the last three months, are being slowly done to death on the pontoons.”[138]

At the same time in America, while women abroad like Dmitrieva actively and purposefully combined the women’s movement with the leading edge of proletarian socialist class warfare, Victoria Woodhull herself was involved in the overt and accelerated separation between working class mass organization and ‘feminism.’ Friedrich Sorge, a Marxist leader of the I.W.A. in America, pointed out how Woodhull’s social-reformist grab-bag of woo-woo investment banker lifestyle and elitist grandstanding “tried to force the workingmen to kill their time with idle talk about women’s rights and suffrage, universal language, social freedom‘-a euphemism for Free Love-’every possible kind of financial and civil reform and the like.”[139] As a stark example of this endlessly circuitous ‘idle talk’ in the I.W.A.’s general councils, the Minutes of the First International Workingmen’s Association meetings gives some indication:

Citizen Engels then proceeded with the reading of the General Statutes.

Citizen Eccarius proposed and Citizen Hales seconded that the word “persons” should be substituted for “men” in the declaration, upon the ground that the word “men” was generally understood as being a limitation to one sex.

Citizen Engels thought it was generally understood “men” was a generic term including both sexes.

Citizen Jung supported the proposition. He thought that while we understood the word in that sense, many outside the Association understood it differently[140]

Upon investigation, Eccarius[141] among others later turned out to have likely been in the direct pay of Woodhull’s organization and had to resign from the I.W.A. after refusing to send Marx’s criticisms to the ‘reformist’ American Section 12. Sorge and the American Marxists were livid at these events but made clear that they were not disputing Woodhull’s or the Section’s “right to have their particular views on the women’s question, religion, free love, etc.,… what was disputed was the right to make the I.W.A. responsible for this”[142] Marx himself grew more and more uncompromising with this turn of events, although he had celebrated the American movement’s forward-thinking position on sexual equality as compared to French workers’ movement prospects. Upon seeing the extent of Miss Woodhull’s opportunism, Marx expelled the first female American Presidential candidate from the I.W.A. on the grounds that her Section was “constantly at pains to inform the world that the International was not a workers’ organisation, but a bourgeois one.”[143]

In the 1880s, Marx’s daughter Eleanor showed “it is necessary to remind [feminists] that with all these added civil rights English women, married and unmarried alike, are morally dependent on man, and are badly treated by him. The position is little better in other civilised lands, with the strange exception of Russia, where women are socially more free than in any other part of Europe.”[144] And this exceptionality was itself to grow and manifest in time, especially as regards women’s involvement in revolutionary politics. Barbara Clements shows that Russia at the turn of the 20th century was host to such divergent and extreme political circumstances that between taking on this immense historical risk or giving over to nihilistic victimhood and disgruntled ‘theoretical’ retreat, “[t]housands of young women made that choice in the period 1890-1910, with the consequence that Russia ended up with more female radicals than any other nation in Europe.”[145]

In the early 1900s industrialized West however, this problem of ‘propriety’ and an emerging ‘New Woman’ had an even more flattening effect within middle class women’s ‘activism.’ Olive Schreiner passionately writes, not without some basis, that a rise of prostitution and dissolved families in modernity was a direct result of industrial mechanization: “Our spinning-wheels are all broken; in a thousand huge buildings steam-driven looms, guided by a few hundred thousands of hands ( often those of men ) produce the clothings of half the world; and we dare no longer say, proudly, as of old, that we and we alone clothe our people.”[146] Schreiner attempts to emphasize the contradictory liberatory aspects of modern technological development by putting forward female control/proprietorship as a way out of the madding whorl of wage labor. While the American Marxist Daniel De Leon attacked[147] Schreiner’s undialectical position referencing her misplaced emphasis on ‘Justice,’ the eugenicist elitist female doctor Arabella Kinealy rhetorically assailed Schreiner and others by outlining that “Feminist leaders… claim as jealously the undivided loyalty and subjection of their flock as ever Tyrant-Men demanded of the sex.”[148] For Schreiner then, with or without ‘social reformist’ intentions and a self-convinced political interest, the ‘feminism’ of such writing moves often in a more masochistic direction here, “[i]t is not against man we have to fight but against ourselves within ourselves.”[149] Masoch himself all but worshiped a heroic woman fighting on the police barricades in 1848, “an amazon with a pistol in her girdle, such as he loved to later depict.”[150] Here in both places there is also to be seen a neglect of class struggle and its being overlooked in a self-obsessed manner.

Some of these Western European ‘radical’ socialist feminists were able to travel to the U.S.S.R. in the 1920s, but even the more pro-Soviet among them still retained a vastly alienating elitism. Magdeleine Paz, after giving a peasant woman uncharacteristically lavish gifts, complained that the woman threw herself at Magdeleine’s feet, “she groveled like a squaw!... Wasn’t this thing at my feet one of those cringing worms who reared themselves at their master’s whistle?... This woman abasing herself wasn’t [herself].”[151] Saying ‘you’re welcome’ and moving on was too undignified for this high-minded Western radical. Despite such examples of psychological cleavage, part of one’s involvement in a working class movement does involve a necessary amount of ‘self-criticism’ that someone like Kollontai was able to show throughout her decades of involvement in the CPSU. She also recognized that, “[o]nly if [the fighting workers] are firmly united amongst themselves and, at the same time, one with their class party in the common class struggle, can women workers cease to appear as a brake on the proletarian movement and march confidently forward, arm in arm with their male worker comrades to the noble and cherished proletarian aim -towards a new, better and brighter future”[152]

Yet Kollontai and other women involved in the real work of socialist construction after 1917 could also bring upon themselves their own undoing, and commit many of the same kinds of mistakes that also undermined men in revolutionary work. Some of these were peculiar to Kollontai’s own predicament. Lenin grilled Klara Zetkin on the Western Marxist tendency to divert practical organization with endless ‘idle talk’ once more. In constructively reproaching Zetkin, Lenin says “I was told that questions of sex and marriage are the main subjects dealt with in the reading and discussion of evenings of women comrades. They are the chief subject of interest, of political instruction and education. I could scarcely believe my ears… surrounded by counter-revolution of the whole world… [the situation] requires the greatest possible concentration of all proletarian, revolutionary forces to defeat… counter-revolution. But working women comrades discuss sexual problems… What a waste!”[153] Kollontai apparently agreed in theory, though in practice, this involved other matters.

The above is something the feminists cannot and do not wish to understand… However, each such success, each new prerogative attained by the bourgeois woman, only puts into her hands yet another instrument with which to oppress her younger sister, and would merely deepen the gulf dividing the women from these two opposing social camps.

Their interests would clash more sharply, their aspirations become mutually exclusive. Where, then, is this universal ‘women’s question’?[154]

Some years prior, Daniel De Leon wrote from America demonstrating just how much:

“machinery, together with concentrated capital, [stripped] man as well as woman of one household function after another… as fast as sewing, spinning, etc, was taken from the house-wife, carpentering, tinkering, etc. was also taken from the pater familias, production tended evermore to be carried on en masse, for sale, ever less for home use or consumption; and thus… depriving man as well as woman of the function of procreation… WOMAN, as well as MAN, figures among the pestiferous tyrants as the beneficiary of this family-destroying and race-unsexing system of capitalism.”[155]

Formerly enslaved revolutionary Black American women around this time period could also unmistakably recognize that a “woman question” was being asked and could also give an answer, though the ‘feminists’ of the time and many alive today might find it distasteful:

Still, I hold now, as I have ever held, that the economic is the first issue to be settled; that it is woman’s economical dependence which makes her enslavement to man possible... I have too much faith in the purity of my sex, to believe there are any considerable number of them, who would submit to men’s domination, if it were possible for them to make an independent living, without having to submit to the debasing factory rules of today?... These are in brief my views upon the sex question, for this reason I have never advocated it as a distinct question[156]

Recollecting Rabotnitsa and the end of Zhenotdel

I absolutely do not believe in happiness, but believe only that it is possible to forget about unhappiness, one’s own and others’ (and that only partly), by fulfilling one’s duty[157] - Olga Ulyanova after the execution of her brother Alexander

Lenin himself gave warnings to several prominent Soviet women about major risks to be confronted. These groups had to first pass through some of those potential follies. The privileging of certain ‘emotional’ or ‘subjective’ questions over practical and revolutionary everyday habits has its expected outcomes. Stalin also gave a prescient warning in his statement published in the woman’s Party theoretical journal Kommunistka in 1923 about dangers that were ahead: “[Class-conscious Woman] can bring in this matter tremendous benefit if she frees herself from ignorance and darkness. And vice versa: she can slow down the whole matter if she continues to remain in captivity of ignorance.”[158] This not only applies to ‘backward’ peasant women, but also to those who insisted upon an adventurist direct ‘intervention’ in those ‘backward’ women’s lives.

After the 1917 Revolution, the Bolshevik women continued to agitate and win over the working masses and peasantry throughout the Civil War period. One instance features “Bolshevik woman worker Kruglova… [and] workers of her factory [fighting] against the soldiers… and some Cossack troops. The Cossacks turned on the marchers ready to charge. Their officer cried: “Who are you following? You’re being led by a baba [old hag, a peasant woman]!”[159] Firing back “Kruglova replied, ‘I am not a baba, but a rabotnitsa [an independent female factory worker], wife and sister of the soldier.’ This short interchange signified the transformative potential of revolutionary discourse. Kruglova demanded to be identified as a rabotnitsa, or an independent civic subject, but at the same time she used kinship metaphors to represent her affiliation with the soldiers.”[160] The Revolution itself was what brought about this outpouring of class consciousness and militant attitude toward one’s duty to the proletarian struggle. “L. Ded, an apprentice who became a Bolshevik in 1917, wrote that after she heard a Bolshevik speech, ‘Everything became clear and understandable to me.’ An unnamed hospital employee echoed these sentiments in a letter to Pravda in 1919. ‘I am a worker,’ she wrote, ‘and only now do I see who buries our rights deep and does not want us to be free.’”[161]