Trump's Trade War against China

How Trump’s Economic Nationalism Charts the American Warpath

Intro

On April 2nd, President Donald Trump signed an executive order imposing reciprocal tariffs against a range of nations, with the People’s Republic of China singled out for especially punitive treatment. As of this writing, the levy on Chinese goods has escalated to 145%.[1] [2] In the aftermath, a familiar chorus of Western media pundits and online commentators has proclaimed the impending collapse of China’s economy, predicated on the assertion that China remains fundamentally dependent on access to the American consumer market.

But does this assertion bear weight? This article will examine the economic rationale underpinning Trump’s tariff escalation and, more importantly, assess the capacity of the Chinese state to navigate and withstand such external pressures, sustaining economic growth through diversification, domestic demand and regional and geopolitical realignment.

How China can respond

“The Chinese economy is an ocean, not a small pond. A storm can overturn a small pond, but it cannot overturn the ocean.” — Xi Jinping, 2018/11/5 [3]

A common claim among advocates of American tariffs is that China, as an export-driven economy, relies heavily on access to the U.S. consumer market, and that cutting off this access will cripple its growth. But is this true, or is it a misreading of China's economic structure? On April 6th, an article from an anonymous contributor was published on People’s Daily, a state-owned media pundit. The article’s title was dubbed “Focus on doing your own thing and enhance confidence in effectively responding to the impact of US tariffs.”[4]

A substantial majority (85%) of Chinese firms engaged in export nevertheless conduct the bulk of their trade within national borders, deriving no less than 75% of their total revenues from domestic sales. Moreover, the centrality of the American market to China’s export apparatus has diminished: the United States accounted for 19.2% of Chinese exports in 2018, a figure that had fallen to 14.7% in subsequent years, signaling a gradual decoupling from what was once a hegemonic commercial relationship.[5]

China’s dependence on exports as a driver of economic growth has markedly declined over the past two decades, with the export share of its GDP falling from a peak of 36% in 2006 to merely 19.7% by 2023. This shift stands in stark contrast to global trends: the European Union, for instance, derives 51.9% of its GDP from exports; East Asia, 30.2%; Latin America and the Caribbean, 25.2%; Sub-Saharan Africa, 25.6%; and the Middle East and North Africa, 46.3%.[6] In sum, China’s contemporary economic architecture is far less contingent upon external demand than that of comparable regions, reflecting a deliberate and strategic reorientation toward domestic resilience and endogenous growth.

This relative insulation becomes even more evident when examined through the lens of bilateral trade with the United States. Chinese exports to America constitute a mere 2.5% of China’s GDP—an almost negligible fraction when juxtaposed with Vietnam, where exports to the US amount to a staggering 30% of GDP and comprise 30% of total export volume as of 2025.[7] As of 2023, Mexico’s figure stands at 27.4%, while Canada’s sits at 20.6%. Meanwhile, total US imports account for only 0.53% of China’s GDP.[8] Altogether, the sum total of Sino-American trade comprises approximately 3.03% of China’s GDP, underscoring how marginal the American market has become in the wider Chinese economic calculus.

The asymmetry is even more pronounced when viewed from the inverse: it is the United States, not China, that finds itself strategically dependent. A vast array of consumer goods, capital equipment, and intermediate inputs critical to American supply chains are sourced from the People’s Republic. In several categories, American reliance exceeds 50%, with few viable substitutes available in the global market in the short term—a vulnerability acknowledged even in official discourse.[9]

Notably, on April 12th, the Trump administration’s selective exemptions on tariffs, particularly on electronic goods such as smartphones, computers, and related components, serve as an inadvertent concession to this structural dependence.[10] The underlying rationale is not difficult to discern: China is the dominant supplier in these sectors, providing 79% of all U.S. PC monitor imports, 73% of smartphones, and 66% of laptops.[11] Given that consumer electronics constitute China’s foremost export to the American market [12], this represents not merely a tactical exemption but a strategic victory, one that exposes the limits of American decoupling rhetoric and reaffirms the enduring gravitational pull of Chinese industrial capacity.

Another common talking point within American policy circles is the supposed dependence of China on US soybean exports, particularly in sustaining its vast livestock sector, wherein soy serves as the primary feedstock. Nevertheless, this narrative, while rhetorically convenient, does not withstand scrutiny. Far from being an intractable dependency, China has both the capacity and geostrategic intent to curtail its reliance on American soybeans. As outlined by the China Academy [13], there are three principal reasons why this transformation is not only possible but already underway:

China is actively developing high protein strains of corn, which could replace soybean as a feed source for China’s livestock. Ordinary corn typically has a protein content of 8%, but China’s high-protein corn can reach up to 30%. Each percentage increase can reduce China’s soybean consumption by 8 million tons.

Brazil is emerging as an alternative soybean supplier. By 2025, China’s soy imports from America will account for 18% of its total, while imports from Brazil take up 74%. China already imports most of its soy from Brazil.

China is cultivating purple alfalfa which has a quick maturation frame of 25 days, can be planted and harvested relatively quickly despite the lower protein content relative to soy. Additionally, alfalfa has reproductive health benefits for pigs, further enhancing the feed’s viability as an alternative to soy.

In response to mounting external pressures and sustaining domestic growth, China has undertaken a series of countercyclical fiscal measures aimed at reinforcing its industrial foundation and preserving its sovereignty. Among these, the state has raised its fiscal deficit rate to 4% and issued treasury bonds to bolster investment in what are officially designated as the “two new” and “two heavy” policy initiatives.[14] The “two new” policies pertain to promoting a new round of large-scale industrial and infrastructure equipment upgrades and the replacement of old consumer goods with new ones, a clear signal of the state’s intent to stimulate both productive capacity and domestic consumption. Meanwhile, the “two heavy” policies are concerned with the execution of major national strategies and construction of security capabilities in key areas[15] underscoring the regime’s long-term commitment to sovereignty and infrastructural resilience in the face of a deepening geopolitical rivalry.

By steadfastly prioritizing the domestic market, China can target larger infrastructure and industrial initiatives and projects, thereby safeguarding its economy from external shocks. Chief among these priorities is the energy sector, long regarded as the “heart” of the economy, given that every stratum of production, from the primary to the tertiary, is inextricably dependent upon a stable and expanding supply of electricity. Notably, on April 2nd, the day the US unveiled its tariff escalation, Beijing responded with resolve, announcing a new slate of major low-carbon development projects for the year ahead. These initiatives span both the manufacturing and energy sectors, signaling a dual commitment to the construction of an “ecological civilization” and industrial modernization,[16] ranging from constructing large battery storage facilities, large wind farms, green hydrogen, zero carbon steel manufacturing, low carbon silicon manufacturing and underwater low carbon data centers.[17] Support for these large scale and capital intensive projects can drive economic growth, while simultaneously targeting green transition plans. In contrast, Trump believes that, rather than deepening environmental reform, the answer to AI’s large-scale energy demands is coal.[18]

In its ongoing efforts to recalibrate the economy towards domestic consumption, China has introduced measures aimed at reducing work hours and thereby stimulating consumer spending. On March 16, the State Council released a communique titled “The Special Action Plan to Boost Consumption,”[19] which emphasizes the importance of adhering to labor laws concerning work hours. The plan specifically calls for the prevention of illegal overtime, the guarantee of paid annual leave and the protection of workers’ rights to rest.

Local party organizations, unions, social security departments and human resource departments shall accordingly strengthen and increase supervision of the rest and leave system. An additional suggestion is that schools should actively seek to explore the establishment of spring and autumn holidays in light of actual conditions.[20] As such, several major Chinese companies have begun implementing reforms to reduce excessive work hours. For instance, Midea has enforced a 6:20 p.m. clock-off policy, Haier has adopted a five-day workweek, and DJI mandates office closures by 9 p.m. These changes represent a significant departure from the traditional "996" work culture (9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week) that has been prevalent in China's tech and manufacturing sectors. The employee response is said to have “definitely been… positive.”[21]

With the State Council enforcing stricter scrutiny on the enforcement of the 44-hour workweek, this reduction in work hours can boost consumption. This is achieved through changes in lifestyle patterns that result in additional free time. By fostering a healthier work environment, the Chinese government aims to incentivize individuals to spend this free time engaging in activities that lead to consumption, such as hobbies, travel, or leisure activities, thereby supporting economic growth.

In addition, China has leveraged its geopolitical position in the rare earth elements (REEs) sector to maintain economic supremacy amidst escalating trade tensions. On April 4, in direct response to heightened US tariffs, Beijing imposed stringent restrictions on seven heavy rare earth elements, including terbium and dysprosium, materials indispensable to the production of semiconductors, electric vehicles, and advanced military technologies.[22]

This move underscores China's near monopoly in the global REE market, where it accounts for approximately 90% of processing capacity. The restrictions have already led to significant disruptions, with US companies like MP Materials halting exports to China and accelerating domestic processing initiatives. However, the US faces substantial challenges in establishing a self-sufficient REE supply chain, given the long lead times and regulatory complexities involved in developing new mining and processing facilities.

The implications of China’s export controls are significant, particularly for the US defense sector, which relies heavily on REEs for the manufacturing of drones, robotics and other advanced military equipment necessary to achieve a global lead in warfare.[23] The sudden restriction of access to these critical materials poses a significant threat to the operational readiness and technological superiority to American military forces.[24]

Not only does China exercise near-total command over the global production of rare earth magnets, controlling an estimated 90% of global output, it also dominates the entire rare earth element value chain, accounting for between 85% and 90% of global capacity from initial extraction to final smelting.[25] This vertical integration grants the Chinese state unrivalled leverage over the supply of materials essential to high-technology and defense manufacturing. China also refines 68% of the world’s cobalt, 65% of its nickel, and 60% of its lithium—all processed to the exacting standards required for use in electric vehicle batteries.[26]

The Chinese government is cognizant of the US’ reliance on China’s rare earth elements industry, with a 2019 article elucidating that these resources are not merely export commodities but instruments of national interest, explicitly designed to serve domestic needs first. In the same commentary, it was noted that the US sought to utilize products manufactured with Chinese-supplied rare earths as tools to counter and suppress China’s development.[27]

As of April 15th, China has effectively barred Boeing from further sales to its domestic airline carriers, a decisive move that severs access to one of the American aerospace giant’s most lucrative markets.[28] This is likely to catalyze deeper cooperation with Airbus and accelerate state-led investment into domestically produced COMAC C919, thereby advancing China’s longstanding objective of cultivating a sovereign, globally competitive civil aviation industry.

As of April 25, China has also cancelled imports of pork from America. China cancelled orders for 12,030 metric tonnes of American pork, the largest cancellation since May 2020. China has also raised the effective tariff rate on American pork shipments to 172%.[29] American pork makes up only around 5.8% of Chinese pork imports, but China is the 3rd largest market for American pork exports. To replace the slight deficit of pork imports, China has strengthened trade deals with Spain.[30]

According to People’s Daily, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China anticipated the escalation of economic hostilities by the US, with a renewed round of tariffs, intensifying an incipient trade war under the guise of reciprocal economic policy. In preparation, the Central Committee’s Economic Work Conference undertook comprehensive planning to confront a new phase of containment by the US against China.[31] The conference emphasized the expansion and refinement of macroeconomic tools, stressing the necessity of improving the range of policies used, strengthening the capacity for extraordinary counter-cyclical adjustments and enhancing the forward-looking, targeted and effective nature of macroeconomic regulation in response to changing conditions.[32]

Indeed, as of this writing, it appears that Trump has begun to grasp the full magnitude of the geopolitical and economic consequences it has triggered. On April 23rd, the Trump administration is now considering a partial rollback of tariffs on Chinese imports, slashing the punitive 145% rate to a range of 50% to 65% in certain cases.[33] This follows an earlier concession in which all tariffs on consumer electronics were rescinded. That it is the US, not China, initiating a retreat on two separate occasions makes the balance of power abundantly clear. It is Washington buckling under the pressure, not Beijing.

In response to Trump’s goodwill however, China as of April 26th, allegedly has waived retaliatory tariffs on some US chip imports. The report said at least eight integrated circuit (IC)-related tariff codes were exempted from levies imposed earlier this month in response to US President Donald Trump’s tariffs on Chinese products. However, China has maintained tariffs on memory chips. The nature of this report is, however, unconfirmed, as the article was deleted shortly after it was posted and they merely cited “industry sources.”[34]

Chinese spokesperson He Yaodong, however, said that the only way for Trump to resolve the issue is if all unilateral tariff measures against China were removed. In addition, Chinese spokesperson Gao Jiakun denied that America and China were in contact regarding any consultations or negotiations on the tariff issue.[35]

Trump: America’s Hirohito

Among the clerisy of the American foreign policy establishment, few developments have inspired greater dread than the reintroduction of protective tariffs by the Trump administration. What appears as an archaic reversion to economic enclosure is, in fact, a vital rupture in the global financial system. For all their bluster and incoherence, Trump’s tariffs represent the expression of a deeper, structural shift in geoeconomic relations that indubitably portends to the decline of the Atlanticist world-system.

The return of tariffs adumbrated an instinctive grouping of a wounded empire toward self-preservation through confrontation. Far from a quixotic attempt to restore the vanished America of post-war Fordism, Trump’s embrace of economic nationalism strips bare the American project of its humanitarian cloak and reorients it towards its founding logic–violence, expansion and imperial control. Far from a random aberration, this reflects a “general law” inscribed in the very genetic makeup of capitalism, that being the tendency of Capital’s inevitable expansion by which capitalism solves its immediate problems and postpones its contradictions. Karl Marx shows that capitalism is structured as a “peculiar machine whose evolution is (dialectically at one with its breakdown, its expansion at one with its malfunction, its growth with its collapse.”[36]

In moments of crisis, such as domestic industries threatened by foreign competition, the state is forced to introduce tariffs to protect these sectors, shore up employment and stabilise its domestic economy. The strength of capitalism indeed resides in the fact that its axiomatic is never saturated, that it is always capable of adding a new axiom to the previous ones. The return to protection or militarisation illustrates the inevitable dialectic of a world-system past its zenith, forced to confront its own logic.

In the world that emerged from 1945 and accelerated after 1991, America dominated not merely through its military might but through its unprecedented ability to command global finance, define legal norms and coerce foreign states with the promises of the free market and modernisation through predatory institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

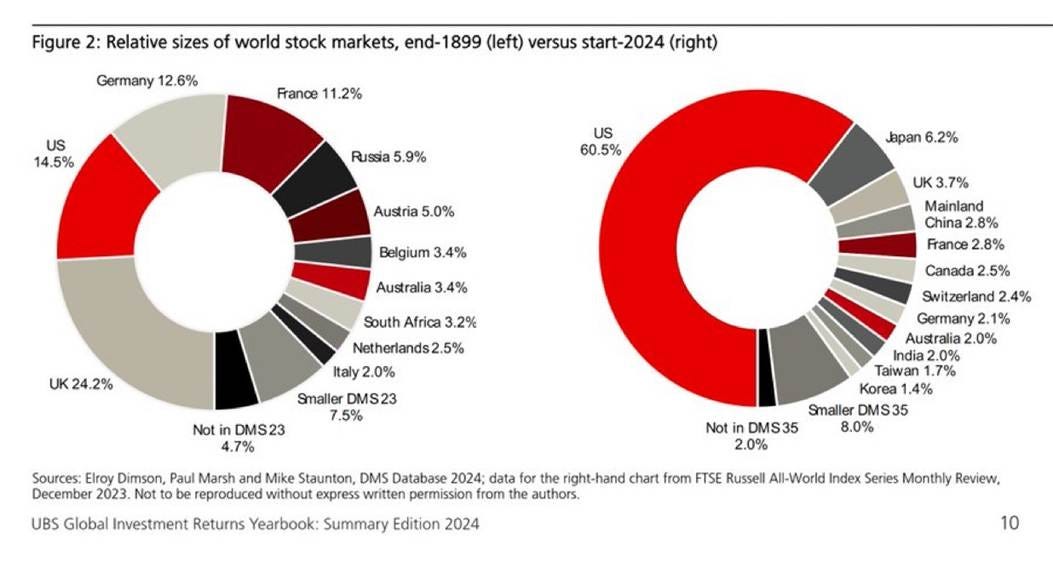

This regime depends on the centrality of the US dollar, the ubiquity of American consumer culture, and the convergence of global elites toward Wall Street. With the concentration of monopoly finance capital to an unprecedented degree, capitalists from all over the world store their wealth in largely US dollar-denominated assets. The US hosts 60.5% of the total value of global stock markets and foreign investors own about 40% of US corporate equity in 2019.

Yet, this world is now decaying. The edifice of American finance, propped up by global consumption of American debt and undergirded by the illusion of consensus, is fracturing under the weight of its own contradictions. It is at this moment that the Trump tariffs acquire their true significance, not as mere economic instruments, but the embryonic organs of a new order. Trump imposed tariffs not because he individually wished to do so, but because historical actors are constrained by conditions that are not of their making and must therefore enact measures reflecting the inexorable logic of historical development.

As G.W.F. Hegel wrote,

“…such individuals had no consciousness of the general Idea they were unfolding, while prosecuting those aims of theirs; on the contrary, they were practical, political men. …For that Spirit which had taken this fresh step in history is the inmost soul of all individuals; but in a state of unconsciousness which the great men in question aroused.” [37]

For Hegel, the cunning of reason means precisely that historical progress unfolds not through the deliberate actions of individual figures, but rather through their seemingly arbitrary and self-interested decisions which inadvertently serve the unfolding of a higher, universal historical logic—what Hegel calls the “universal Idea”.

From the purview of accelerationism, these developments must be affirmed. Trump, although unwittingly, has set the US on a path of decline. By initiating the reindustrialisation of ‘upstream’ sectors, such as steel, microelectronics, rare earth refinement, munitions, and heavy manufacturing, he has begun the pivot toward militarisation.[38] The explicit rationale of these tariffs, namely the restoration of a hollowed-out military-industrial complex is an admission of vulnerability, exposing the fragility of a superpower that has for decades outsourced its industrial base and entrusted its supply chains to the whims of the global market.

In declaring the need to rebuild, Trump acknowledges the indeterminacy of a world where the present Weltgeist is blowing eastward, not retreating the empire, but purifying it, stripping it of its moral pretensions and reducing it to its bare essence: territorial expansion, resource capture and geoeconomic supremacy. The system cannot not expand; if it remains stable, it stagnates and dies; it must continue to absorb everything in its path, to interiorize everything that was hitherto exterior to it. Tariffs may redirect the flows of capital, but they do not arrest the system’s relentless expansion, nor the conflicts it inevitably generates. Instead, they re-emerge later, often more acutely, and, in this case, in a final military confrontation with China.

In Anti-Oedipus, Deleuze and Guattari wrote:

“Social machines make a habit of feeding on the contradictions they give rise to, on the crises they provoke, on the anxieties they engender, and on the infernal operations they regenerate. Capitalism has learned this, and has ceased doubting itself, while even socialists have abandoned belief in the possibility of capitalism's natural death by attrition. No one has ever died from contradictions. And the more it breaks down, the more it schizophrenizes, the better it works, the American way.” [39]

Hence, the growing fixation of the Trump administration on Greenland is a historical-material imperative rooted in the desire for untapped reservoirs of rare earth elements crucial for the production of radars, missile guidance systems, semiconductors and other wartime technologies. Just as Japan in the 1930s turned to Manchuria to break the impasse of economic stagnation and siphon the materials necessary for war, so too does American now look to Greenland as the mineral lifeline for its reindustrialization. The success of Imperial Japan consolidating domestic support for war through the economic gains derived from Manchuria reflects the same principle that territorial expansion can alleviate economic stagnation, restore national pride and unite a fragmented populace through military-industrial might. The oligarchy of Silicon Valley, exemplified by figures such as Elon Musk, sees clearly the importance of new frontiers beyond American borders insofar as they can fuel the military-industrial complex. Lithium from Bolivia, oil from Venezuela and rare earths from Greenland, each a mineral key to the imperial machine.

Moreover, by enabling Japan and Australia to field more autonomous, aggressive military postures, the United States frees itself from the fiscal drain of subsidizing their defense while forging stronger, more capable junior partners against China in the pacific, simultaneously preserving American hegemony while discarding its superfluous expenditures. The liberal dream of endless integration, depoliticized trade and a ‘rules-based’ harmony is revealing itself to be a fantasy. The US reasserts itself not as a manager of global affairs, but a political actor in the Schmittian sense: drawing lines, demarcating enemies and preparing for war.

This doctrine becomes even more coherent when viewed in light of the growing global bifurcation. China’s recent imposition of massive docking fees on foreign ships, upwards of $10 million per entry, in tandem with reciprocal tariffs on the US signals a strategic closure of its own markets to the West. The era of trading with both is coming to an end. Nations will be compelled to choose subservience to the American military-economic bloc or integration within an emergent Sinocentric world-system. Trump’s tariffs serve precisely this purpose–to tear apart the ambiguity that has for decades allowed countries to simultaneously court America and China.

As Marx stated, “force is the midwife of every old society which is pregnant with a new one.”[40] The American ruling class cannot resolve its own contradictions through peace; it requires crisis and war to reproduce itself, but in charting such a path, it confirms the inevitability of its own exhaustion. The US is a centrifugal empire, it depends on perpetual outward motion, it must lash out in every direction because it cannot stand still; its inner equilibrium is contingent upon a state of external disorder. For this reason, the US casts China not as a competitor, but an existential threat. As Trump’s National Security Advisor, Michael Waltz, said: “we are in a Cold War with the Chinese Communist Party” because China is an “existential threat to the US with the most rapid military build-up since the 1930s.” [41]

China is the enemy par excellence because it represents an alternative, anti-hegemonic centre of power. China, unlike the US, does not universalise itself through military occupation; it does not ‘dominate’. China is centripetal, it attracts towards itself; its “dominance” thus consists in its ability to be a ‘Sinomorphing’ force setting civilisational standards through integration into a common Eurasian industrial space.

This distinction, according to Carl Schmitt, corresponds to the logic of enmity:

“An enemy is not someone who, for some reason or other, must be eliminated and destroyed because he has no value. The enemy is on the same level as I am. For this reason, I must fight him to the same extent and within the same bounds as he fights me, in order to be consistent with my own understanding of the concept of the enemy.” [42]

Thus, Trump’s tariffs are axiomatic to the decline of American imperialism; a tacit admission of the deep ontological indeterminacy in the world itself that the US is struggling to navigate against the backdrop of a rising China. Some have suggested a return to a Monroe Doctrine style imperialism, where the language of protection under the guise of preventing European interference in the affairs of the Western Hemisphere cloaked the logic of domination. As Frederic Jameson wrote, “Crises and the catastrophes appropriate to this present of time, which like those of the past are both the same as what preceded them, but also different and historically unique.” [43]

The introduction of tariffs, and the discourse surrounding it, indicates a return to an old form of legitimation on a new basis, necessary to sustain US imperialism. Trump is breaking with the form the system has hitherto taken in order to survive, and in doing so hopes to preserve its fundamental content. As Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa wrote in his novel, The Leopard, things need to change so that they can stay the same. [44]

SOURCES

Bloomberg News. (2025). Badger Hair and iPhones: Where US-China Decoupling is Hardest. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-04-09/badger-hair-and-iphones-where-us-china-decoupling-is-hardest?embedded-checkout=true [Accessed: 15th April 2025].

Bloomberg News. (2025). China Orders Boeing Jet Delivery Halt as Trade War Expands. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-04-15/china-tells-airlines-stop-taking-boeing-jets-as-trump-tariffs-expand-trade-war?embedded-checkout=true [Accessed: 17th April 2025].

Bradsher, K. (2025). China Halts Critical Exports as Trade War Intensifies. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/13/business/china-rare-earths-exports.html [Accessed: 5th April 2025].

Chen, W. (2025). China said to waive retaliatory tariffs on some US chip imports in sign of trade war thaw. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/tech/tech-war/article/3307881/china-said-waive-retaliatory-tariffs-some-us-chip-imports-sign-trade-war-thaw [Accessed: 16th April 2025].

Cohen, J. (2023). Resource realism: The geopolitics of critical mineral supply chains. Goldman Sachs. https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/resource-realism-the-geopolitics-of-critical-mineral-supply-chains [Accessed: 4th April 2025].

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1972). Anti-Oedipus. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Dempsey, H., Hodgson, C. & Smyth, J. (2025). How critical minerals became a flash point in US-China trade war. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/aa03e3b0-606d-4106-97dc-bac8ad679131?utm_source=chatgpt.com [Accessed: 25th April 2025].

Department for Environmental Resources. (2025). 关于向社会公开征求《绿色低碳先进技术示范项目清单(第二批)》意见的公告. National Development and Reform Commission. https://yyglxxbsgw.ndrc.gov.cn/htmls/article/article.html?articleId=2c97d16c-9324f814-0195-f4109999-002b#iframeHeight=810 [Accessed: 3rd April 2025].

Fouda, M. (2025). White House says tariff rate on most Chinese imports is now 145%. Euro News. https://www.euronews.com/2025/04/11/white-house-clarifies-tariff-rate-on-most-chinese-imports-is-actually-145 [Accessed: 12th April 2025].

Funk, J. (2025). The US has a single rare earths mine. Chinese export limits are energizing a push for more. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/rare-earths-trump-tariffs-china-trade-war-effd6a7ec64b5830df9d3c76ab9b607a [Accessed: 20th April 2025].

Garrido, C. (2025). Trump as Today’s FDR: On U.S. Imperialism Taking a New Form. Midwestern Marx. https://www.midwesternmarx.com/articles/trump-as-todays-fdr-on-us-imperialism-taking-a-new-form-by-carlos-l-garrido [Accessed: 16th April 2025].

Garrido, C. (2025). Trump is Merely Using Change to Maintain U.S. Hegemony Unchanged. The China Academy. https://thechinaacademy.org/trump-is-merely-using-change-to-maintain-u-s-hegemony-unchanged/ [Accessed: 15th April 2025].

Guarascio, F. (2025). Vietnam’s US exports account for 30% of GDP, making it highly vulnerable to tariffs. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/markets/vietnams-us-exports-account-30-gdp-making-it-highly-vulnerable-tariffs-2025-02-25/ [Accessed: 15th April 2025].

Halpert, M. (2025). Trump exempts smartphones and computers from new tariffs. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c20xn626y81o [Accessed: 15th April 2025].

Hegel, G.W.F. (2001). The Philosophy of History. Ontario, Batoche Books.

Hunnicutt, T. (2025). White House would consider cutting China tariffs as part of talks, source says. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/white-house-mulls-slashing-china-tariffs-between-50-65-wsj-reports-2025-04-23/ [Accessed: 23rd April 2025].

Jameson, F. (2011). Representing Capital. London, Verso.

Jennings, R. & Chen, F. (2025). ‘It’s everything’: 5-year-high pork cancellation signals China weaning off US farm goods. South China Morning Post.

https://www.scmp.com

[Accessed: 26th April 2025].

Kanetkar, R. (2025). AI needs a lot of energy. Trump says coal is the answer. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/trump-coal-ai-data-centers-executive-order-2025-4 [Accessed: 9th April 2025].

Liu, J. & Gan, N. (2025). Trump’s trade war olive branch met with derision and mistrust inside China. CNN Business. https://edition.cnn.com/2025/04/24/business/china-response-trump-trade-war-softening-intl-hnk/index.html [Accessed: 17th April 2025].

Marx, K. (1976). Capital Volume I. London, Penguin Classics.

Mukherjee, V. (2025). ‘Storms can’t overturn sea’: Xi Jinping’s speech resurfaces amid trade war. Business Standard. https://www.business-standard.com/world-news/xi-jinping-old-speech-us-china-trade-war-donald-trump-125041000729_1.html [Accessed: 15th April 2025].

People’s Daily. (2025). 人民日报评论员:集中精力办好自己的事 增强有效应对美关税冲击的信心. http://opinion.people.com.cn/n1/2025/0406/c1003-40454209.html [Accessed: 7th April 2025].

Schmitt, C. (2007). Theory of the Partisan: Intermediate Commentary on the Concept of the Political. New York, Telos Press Publishing.

World Bank. Exports of goods and services (% of GDP) – China. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.ZS?locations=CN [Accessed: 20th April 2025].

Xinhua. (2025). 中共中央办公厅 国务院办公厅印发《提振消费专项行动方案》. 中国政府网. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/202503/content_7013808.htm [Accessed: 14th April 2025].

[1] Colton, E. (2025). What is Trump’s new Liberation Day and what to expect April 2? Fox News. https://www.foxnews.com/politics/what-liberation-day-what-expect-april-2 [Accessed 2nd April 2025].

[2] Fouda, M. (2025). White House says tariff rate on most Chinese imports is now 145%. Euro News. https://www.euronews.com/2025/04/11/white-house-clarifies-tariff-rate-on-most-chinese-imports-is-actually-145 [Accessed 12th April 2025].

[3] Mukherjee, V. (2025) ‘Storms can’t overturn sea’: Xi Jinping’s speech resurfaces amid trade war. New Delhi. Business Standard. https://www.business-standard.com/world-news/xi-jinping-old-speech-us-china-trade-war-donald-trump-125041000729_1.html [Accessed: 15th April 2025].

[4] People’s Daily. (2025). 人民日报评论员:集中精力办好自己的事 增强有效应对美关税冲击的信心--观点--人民网. http://opinion.people.com.cn/n1/2025/0406/c1003-40454209.html [Accessed: 7th April 2025].

[5] Ibid

[6] World Bank. Exports of goods and services (% of GDP) – China. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.ZS?locations=CN [Accessed: 20th April 2025].

[7] Guarascio, F. Vietnam’s US exports account for 30% of GDP, making it highly vulnerable to tariffs. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/markets/vietnams-us-exports-account-30-gdp-making-it-highly-vulnerable-tariffs-2025-02-25/ [Accessed: 15th April 2025].

[8] Wolf, M. (2025). Predictability is the victim of Trump’s tariff threats. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/f0970c34-715e-4afb-82ec-30022ec3fb44 [Accessed: 15th April 2025].

[9] People’s Daily. (2025). 人民日报评论员:集中精力办好自己的事 增强有效应对美关税冲击的信心--观点--人民网. http://opinion.people.com.cn/n1/2025/0406/c1003-40454209.html [Accessed: 7th April 2025]

[10] Halpert, M. (2025). Trump exempts smartphones and computers from new tariffs. New York. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c20xn626y81o [Accessed: 15th April 2025].

[11] Bloomberg News. Badger Hair and iPhones: Where US-China Decoupling is Hardest. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-04-09/badger-hair-and-iphones-where-us-china-decoupling-is-hardest?embedded-checkout=true [Accessed: 15th April 2025].

[12] Zhu, K. (2025). Which Chinese Products Are Most Exposed to U.S. Tariffs? Visual Capitalist. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/which-chinese-products-are-most-exposed-to-u-s-tariffs/ [Accessed: 2nd April 2025].

[13] Zhai, C. (2025). Trump’s Tariffs Make Chinese Agriculture Great Again. The China Academy. https://thechinaacademy.org/trumps-tariffs-make-chinese-agriculture-great-again/ [Accessed: 11th April 2025]

[14] People’s Daily. (2025). 人民日报评论员:集中精力办好自己的事 增强有效应对美关税冲击的信心--观点--人民网. http://opinion.people.com.cn/n1/2025/0406/c1003-40454209.html [Accessed: 7th April 2025]

[15] Yes, X. (2024). 来,一起认识‘两新’、‘两重’政策! - 求是网. Qiushi. http://www.qstheory.cn/laigao/ycjx/2024-11/14/c_1130219317.htm [Accessed: 1st April 2024]

[16] Department for Environmental Resources. (2025). 关于向社会公开征求《绿色低碳先进技术示范项目

清单(第二批)》意见的公告.National Development and Reform Commission. https://yyglxxbsgw.ndrc.gov.cn/htmls/article/article.html?articleId=2c97d16c-9324f814-0195-f4109999-002b#iframeHeight=810 [Accessed: 3rd April 2025].

[17] List of green and low-carbon advanced technology demonstration projects (second batch). National Development and Reform Commission of the People's Republic of China. https://yyglxxbs.ndrc.gov.cn/file-submission/20250402115327890451.pdf [Accessed: 15th April 2025]

[18] Kanetkar, R. (2025). AI needs a lot of energy. Trump says coal is the answer. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/trump-coal-ai-data-centers-executive-order-2025-4 [Accessed: 9th April 2025].

[19] Xinhua. (2025). 中共中央办公厅 国务院办公厅印发《提振消费专项行动方案》_中央有关文件_中国政府网. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/202503/content_7013808.htm [Accessed: 14th April 2025].

[20] Ibid

[21] Yu, S. & Master, F. In China, whispers of change as some companies tell staff to work less. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-whispers-change-some-companies-tell-staff-work-less-2025-04-08/ [Accessed 12th April 2025].

[22] Funk, J. (2025). The US has a single rare earths mine. Chinese export limits are energizing a push for more. Omaha. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/rare-earths-trump-tariffs-china-trade-war-effd6a7ec64b5830df9d3c76ab9b607a [Accessed: 20th April 2025].

[23] Dempsey, H., Hogdson, C. & Smyth, J. (2025). How critical minerals became a flash point in US-China trade war. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/aa03e3b0-606d-4106-97dc-bac8ad679131?utm_source=chatgpt.com [Accessed: 25th April 2025].

[24] Bradsher, K. (2025). China Halts Critical Exports as Trade War Intensifies. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/13/business/china-rare-earths-exports.html [Accessed: 5th April 2025]

[25] Cohen, J. (2023). Resource realism: The geopolitics of critical mineral supply chains. Goldman Sachs. https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/resource-realism-the-geopolitics-of-critical-mineral-supply-chains [Accessed: 4th April 2025]

[26] Venditti, B. (2024). Visualizing China’s Cobalt Supply Dominance by 2030. VC Elements. https://elements.visualcapitalist.com/visualizing-chinas-cobalt-supply-dominance-by-2030/?utm_source=chatgpt.com [Accessed: 6th April 2025]

[27] Wu, Y. (2019). United States, don’t underestimate China’s ability to strike back. People’s Daily. http://en.people.cn/n3/2019/0531/c202936-9583292.html [Accessed: 16th April 2025]

[28] Bloomberg News. (2025). China Orders Boeing Jet Delivery Halt as Trade War Expands. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-04-15/china-tells-airlines-stop-taking-boeing-jets-as-trump-tariffs-expand-trade-war?embedded-checkout=true [Accessed: 17th April 2025].

[29] Jennings, R. & Chen, F. (2025). ‘It’s everything’: 5-year-high pork cancellation signals China weaning off US farm goods. South China Morning Post. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-04-15/china-tells-airlines-stop-taking-boeing-jets-as-trump-tariffs-expand-trade-war?embedded-checkout=true [Accessed: 26th April 2025]

[30] Timotija, F. (2025). China cancels 12,000 metric tons of US pork shipments. The Hill. https://thehill.com/policy/international/5266321-china-cancels-us-pork-ships/?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAAR6D7e3roqKRIakomSeuVRIKrgk7JBxMDTLzVxVKCPvSdLpUzYf3mPo-DZ8B7g_aem_EwPj3iVLLWLTmRMyIaecTQ [Accessed: 12th April 2025)

[31] People’s Daily. (2025). 人民日报评论员:集中精力办好自己的事 增强有效应对美关税冲击的信心--观点--人民网. http://opinion.people.com.cn/n1/2025/0406/c1003-40454209.html [Accessed: 7th April 2025]

[32] Ibid

[33] Hunnicutt, T. (2025). White House would consider cutting China tariffs as part of talks, source says. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/white-house-mulls-slashing-china-tariffs-between-50-65-wsj-reports-2025-04-23/ [Accessed: 23rd April 2025].

[34] Chen, W. (2025). China said to waive retaliatory tariffs on some US chip imports in sign of trade war thaw. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/tech/tech-war/article/3307881/china-said-waive-retaliatory-tariffs-some-us-chip-imports-sign-trade-war-thaw [Accessed: 16th April 2025].

[35] Liu, J. & Gan, N. (2025). Trump’s trade war olive branch met with derision and mistrust inside China. CNN Business. https://edition.cnn.com/2025/04/24/business/china-response-trump-trade-war-softening-intl-hnk/index.html [Accessed: 17th April 2025].

[36] Jameson, F. (2011). Representing Capital. London, Verso, pp. 142.

[37] G.W.F, Hegel. (2001). The Philosophy of History. Ontario, Batoche Books, pp. 45.

[38] The White House. Regulating Imports with a Reciprocal Tariff to Rectify Trade Practices that Contribute to Large and Persistent Annual United States Goods Trade Deficits. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/04/regulating-imports-with-a-reciprocal-tariff-to-rectify-trade-practices-that-contribute-to-large-and-persistent-annual-united-states-goods-trade-deficits/ [Accessed: 2nd April 2025].

[39] Deleuze, G and Guattari, F. (1972). Anti-Oedipus. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, pp. 224.

[40] Marx, K. (1976). Capital Volume I. London, Penguin Classics, pp. 916.

[41] Garrido, C. (2025). Trump is Merely Using Change to Maintain U.S. Hegemony Unchanged. The China Academy. https://thechinaacademy.org/trump-is-merely-using-change-to-maintain-u-s-hegemony-unchanged/ [Accessed: 15th April 2025].

[42] Schmitt, C. (2007). Theory of the Partisan: Intermediate Commentary on the Concept of the Political. New York, Telos Press Publishing, pp. 85.

[43] Jameson, F. (2011). Representing Capital. London, Verso, pp. 9.

[44] Garrido, C. (2025). Trump as Today’s FDR: On U.S. Imperialism Taking a New Form. Midwestern Marx. https://www.midwesternmarx.com/articles/trump-as-todays-fdr-on-us-imperialism-taking-a-new-form-by-carlos-l-garrido [Accessed: 16th April 2025].

A long piece, with a lot of detail - thanks for posting. I don't have international trade expertise, but I've done a lot of business negotiations. Here's a post from my four part series https://open.substack.com/pub/srikaza/p/the-art-of-the-international-trade?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=1w9b37